Split Toe, One Soul: The Philosophy of the Tabi Shoe

They don't make sense. They never had to.

There’s a particular sound that your steps make when you wear a pair of Margiela Tabis. The solid click of the heel invites those passing by to take notice. Then they turn their heads, and their gaze immediately falls into the split sole sensation on your feet.

The cleft-toed anomalies are Margiela’s swan song, designed to spark conversation. People either worship them or recoil in disgust. Both parties often fail to realise that they aren’t just shoes. They’re history — 15th-century Japan meets Margiela’s runway debut meets the TikTok For You page. Regardless of whether you know the story or not, once you wear them, you never quite walk the same again.

THE SOCK WITH THE SACRED PAST

Before the Tabi became the leading cult fashion shoe associated with Margiela’s “ugly fashion” aesthetic, or the subject of TikTok Tinder date, they had humble beginnings in Edo, Japan (1603-1868). During this period, these split-toed socks were crafted to be worn with thong sandals like zori and geta. They were humble symbols of etiquette, purity, and precision. Tabi signifies spiritual cleanliness and was essential in Shinto rituals, tea ceremonies, and traditional stage performances. Functional and sacred, what more could you want?

This sacred and functional dual role is perfectly captured in Edo-era art. Take, for example, an 1835 woodblock print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi: a kabuki actor mid-pose, his feet wrapped in dark jika-tab.

The split wasn’t just symbolic—it was biomechanical. The toe separation encouraged posture and balance — practical elements rooted in the belief that a well-aligned body fosters clarity of mind. That function still holds today.

They were most popular with the upper class due to the scarcity of cotton, but China becoming a trading partner made them more able to be widely worn. (Interesting consideration — isn’t it?). Commoners wore blue fabric, while the upper classes could wear the more expensive gold and purple. Tabi's colour demonstrated class status, occasion, and intent.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Tabi evolved from socks to footwear. The addition of rubber soles, called the Jika-Tabi, made them the choice boots for outdoor activities and immensely popular among blue-collar workers. As you can see, tabi was ubiquitous in Edo, Japan, and worn by samurai, courtesans, and commoners alike. Centuries later, that same split-toe structure would be reimagined in Paris — not as etiquette, but as avant-garde rebellion.

DOES IT BEEHOVE YOU?

If the original tabi whispered — quiet, clean, ceremonial — Margiela’s tabi boot screamed.

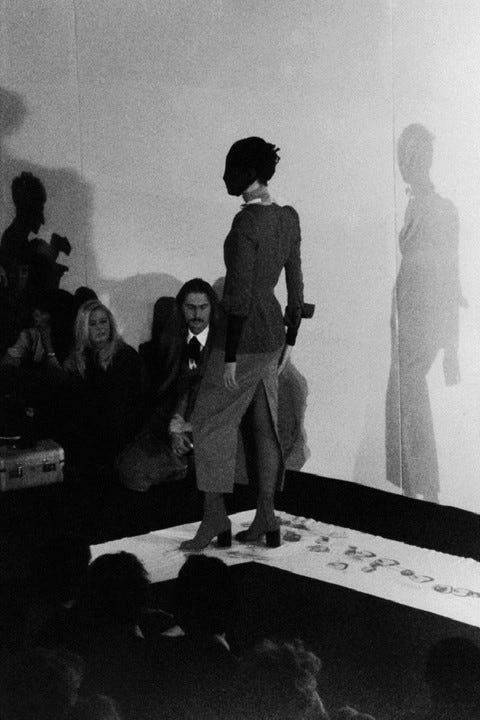

Picture it: Paris, September 1988. A debut runway show and a Belgian designer with something to prove. Enter Martin Margiela. In his debut (!!!) presentation, the faceless, myth-making designer sent models down a white cloth runway in split-toe boots dipped in red paint. The footprint wasn’t a metaphor. It was literal. Cleft-toe marks bleeding across an otherwise pristine stage, announcing something had arrived. Or maybe something had been cracked open.

Margiela’s design carefully toed the line (pardon the pun) between appropriation and appreciation. He consciously identified his Japanese design inspiration, honoured its form, and intentionally rewired it. However, it doesn’t negate the inherent global power dynamics in fashion between the East and West. The West gets to remix, and the East (hopefully) is remembered.

Monsieur Martin took the tabi — an unassuming and ubiquitous sock in Japanese history — and elevated it into a challenge. Fashion commentary. A contradiction. A conversation starter. He wasn’t just referencing heritage, he was re-engineering it. One part industrial hoof, one part silent protest. Critics called them camel feet. Deranged. Repulsive. However, Margiela stood his ground.

The split toe became a symbol. Of nonconformity. Of intellectual cool. Of a new kind of beauty — the sort of beauty that doesn’t beg to be adored.

In the seasons following, the tabi evolved into a Margiela staple. He didn’t just revisit it; he rebuilt it repeatedly—the flats, the thigh-highs, the sandals barely held together by tape—forever awkward, forever defiant, forever Margiela.

And now? It’s not just part of the fashion canon; its illustrious beauty became the standard for entry into it. A boot so polarising it looped back into iconography. No logo is needed. Just two little toes, forever divided, walking to the beat of its own music.

CONFESSIONS OF A TABI GIRL

Mine were my first big girl purchase in London. Armed with GBP and a dream, I entered Harrods looking for a Jellycat and left with a stuffed croissant and a pair of Tabi flats. I’m just a girl. What can I say?

I wasn’t exactly on the hunt for them that day, but a detour into Shoe Heaven helped this angel find her wings. I've had Tabi flats saved on my Pinterest board since 2018 when I first encountered them on high fashion Twitter when I should’ve been paying attention to AP U.S. History.

When I first put them on, I felt like Cinderella fitting her glass slippers. I asked for a size 38, and the sales associate told me I had the last pair. That had to be a sign.

My friend thought they were hideous and couldn’t comprehend why I would spend so much on them. My response? “My bills were paid. This is a 6-year dream coming to fruition, and they fit like a glove.” That seemed like enough. Naturally, I had to celebrate.

Part of Tabi's appeal was that they weren’t easily understood. They didn’t beg to be loved. They just were. For some reason, this felt like my identity in a shoe. Just like the Tabi, I’m walking history but also slightly ahead.

They’re not a flex. They’re a symbol. And when I wear them, everyone knows exactly who I am. Especially me.

Maybe they don’t make sense to you. But that sound? That’s history. And I’m walking in it.

Thank you so much for reading! Stay tuned for the upcoming podcast episode, which will share more of the story of the camel-toed creations.

Talk soon,

Tris <3